Dr. Yizhen Wan

Highlights

- A fall 2020 survey by iimedia shows that the number of new Chinese undergraduate students to US higher education institutions (USHEIs) dropped 90-95% in the academic year of 2020-2021 compared to that in 2019-2020.

- UK higher education institutions (UKHEIs) exerted effective measures to attract Chinese students in the last two decades, resulting in the scale for recruitment of new Chinese students by UKHEIs was about eight times as that by USHEIs in 2019.

- Cancellation of SAT test sites in China by US College Board, which forces Chinese students to have SAT test abroad, was the most important reason causing a sharp decrease of Chinese students to USHEIs in 2016-2019.

- Several practical measures are proposed in this article for USHEIs’ consideration to turn round the adverse situation.

The Number of Chinese Students in US and UK in 2019

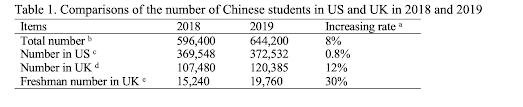

About 644,200 Chinese undergraduate students (CUSs) pursued higher education abroad in the academic year of (AY) 2019-2020, with an increase of 8% compared to that in 2018-2019 (Table 1; Shan, 2020). However, the number of CUSs in U.S. Higher Education Institutions (USHEIs) increased only 0.8% in AY 2019-2020 in comparison with that in 2018-2019 (Table 1; Open Doors, 2020), suggesting that the number of CUSs choosing other outbound countries for higher education had striking increases. For example, UK Universities admitted 19,760 new CUSs in fall 2019, which increased 30% compared to that in 2018 (Table 1; Redden, 2019). Considering the stark differences in the number of the approved HEIs between two countries, the scale for recruitment of new CUSs by UK Higher Education Institutions (UKHEIs) was about eight times as that by USHEIs in 2019.

Population of 372,532 Chinese students contributed ~15 billion US dollars to USHEIs (Royce, 2019), made up 34.6% and ranked at No.1 in the USHEI international student body in AY 2019-2020 (Figure 1) (Open doors, 2020). Therefore, even small shifts in the percentage of Chinese students can make big differences to USHEIs.

b, is the total number of Chinese undergraduate students choosing study abroad.

c, is the total number of Chinese students in US.

d, is the total number of Chinese students in UK.

e, is the number of the new Chinese students in UK.

Many USHEIs reported that the number of new Chinese students have started a sharp drop since AY 2017-2018. For example, the number of Chinese undergraduates in Indiana University declined 30% in 2017. In fall 2019, the number of new Chinese students in Bentley University, the University of Vermont and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln declined 34%, 23%, and 20% respectively (Niewenhuis, 2019).

Figure 1. Top ten places contributing international students to the U.S. higher education institutions (USHEIs). Chinese Students made up 34.6% of the total international students in the USHEI international programs in the academic year of 2019-2020. Data from Open Doors (2020).

Severe Impact of International Education by COVID-19

No doubt, the current international education is severely impacted by COVID-19 pandemic around the world. A survey conducted in September 2020 by iiMedia Research indicated that about 20.7% Chinese students who had previously planned to go abroad for higher education cancelled their pursuit. ~55.2% deferred their plans for study abroad and 24.1% shifted their destination, for example from US to UK, Canada, Hongkong, Singapore, Japan, etc (Shan, 2020). In addition, visa restriction because of the COVID-19 pandemic heavily blocked new Chinese students coming to USHEIs in fall 2020. The number of US visas granted to Chinese students has dropped 99% since April 2020 (Loizos, 2020). Thus, new Chinese students in USHEIs estimates drop of 90-95% in AY 2020-2021 compared to that in 2019-2020 (Shan, 2020). If USHEIs do not take active measures against this drop trend, the total number of CUSs in USHEIs will drop ~65% or more four years later.

The Future Market

Due to economic development of China resulting in emergence of a large number of middle-class-income family (Barclay et al., 2017), experts forecasted that an annual minimum number of 500,000 Chinese students, making up ~1.5% in the Chinese student body (domestic + abroad study), will pursue their higher education abroad in the future 30 years, suggesting annual contribution of 25 billion US dollars to the destination countries. It is a huge market for competition among rivals.

The Most Important Reason Causing Sharp Drop of Chinese Students in US

Numerous reports concluded several major reasons resulting in the recent sharp drop of Chinese students in USHEIs (Skinner, 2019). This article explores several neglected but important reasons for this declining trend.

The mainland of China, the No.1 place sending international students to USHEIs, does not have any test sites in China students for SAT test. Each year from 2016 to 2019 estimated a number of ~110,000 Chinese students take SAT test abroad, such as in Hongkong, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea (Xiao, 2020). In addition, each family of the Chinese students incurred $735 to $1,176 for each SAT test abroad (Lei, 2017; Liu, 2017).

In January 2016, US College Board (USCB) urgently noticed cancelation of the SAT test held in China because of leaked-out test materials (Belkin, 2016). The SAT test sites have not been resumed in China since. Promptly, a large number of Chinese students were shocked by the USCB’s decision and turned to the test of IELTS (approved by the British College Council [BCC]) in 2016 (MEC, 2017). It has been regarded as the most important reason for a sharp slowing-down of Chinese students in USHEIs since 2016 (MEC, 2017; Skinner, 2019).

Over 97% Chinese students aspiring for higher education in USHEIs have since then been unsatisfied with USCB’s ways to resolve the problems (MEC, 2017). Fortunately, the quality of US higher education and global high reputation of numerous USHEIs has sustained the current enrollment, otherwise the USCB’s actions must have made the situation of dropping Chinese students coming to USHEIs even worse.

UKHEIs Struggle Attracting Chinese Students in the Last Two Decades

About 300,000 Chinese students attended IELTS tests each year in the last five years prior to COVID-19 pandemic (Yeung, 2018). BCC did much excellent work in China concerning widespread extension and broad advertisement of IELTS test to struggle for attraction of Chinese students to UKHEIs in the last two decades. For example, the Chinese name for IELTSTM, “雅思”, has become a famous brand in the circle of education in China (Xin, 2019). But both SAT and ACT, the most two important tests for admissions to USHEIs, have not yet had their Chinese names.

A yearly cost of three to five million US dollars invested by BCC and UKHEIs were spent in China to advertise the IELTS tests and attract Chinese student to study in UKHEIs in the last two decades. The number of CUSs in UKHEIs increased from ~6,000 in 2001 to ~ 120,000 in 2019, suggesting an increase of annual revenue paid by Chinese students from 300 million to 6 billion US dollars in the last two decades (IDUKHE, 2020). In fact, their investment has brought high returns to them with a ratio of investment to return as 1: 100-1200.

What Should USHEIs Do to Turn Around the Adverse Trend after the COVID-19 Pandemic?

USCB, the organization representing benefits of USHEIs, should learn from the successful experiences from BCC. USCB should design new SAT materials. Currently, the same SAT materials for one test on the same doomed date are used across the global test sites. Because of the distinct time zones, the test materials are apt to be released by the earlier test participants (Belkin, 2016). In addition, USCB should minimize the repeats of the test materials among different testing times and among the different regions. The same test materials should be used in the ‘real’ same time.

USCB should make spare schemes or remedies against any emergent event, for example, by preparation of a different set of test materials for the spare use.

The organizations responsible for SAT, ACT and TOEFL should set up offices in the major cities of China to manage the tests or to cope with the emergent events. USCB should resume SAT test sites in China and have investment to attract Chinese students to USHEIs. Annual budget of several millions of dollars is needed to spend in China for this purpose. The starting fees for the purpose can be collected from 30 to 50 USHEIs, which ever attracted a large number of CUSs in the last decade (Coudriet, 2019). However, an extra fee of $100 to $200 can be charged from Chinese students for each SAT test and the extra revenue can be used in enhancement on test management in China (Liu, 2017; Zhang, 2020). Chinese students will be satisfied with this amount of the extra charged fee to have the test at home rather than abroad, meaning more money is actually saved to them (Liu, 2017; Zhang, 2020).

Suspicion on theft of hi-tech by foreign students causes wide arguments recently (Cohen & Marquardt, 2019). UK and Canada confront similar threats. However, hi-techs possessed by inbound companies or confidential laboratories are usually not available to foreign students.

References

Barclay, R.T., Weinandt, M., & Barclay, A.C. (2017). The economic impact of study abroad on Chinese students and China’s gross domestic product. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 19(4):30-36.

Belkin, D. (2016, January). SAT canceled in China and Macau over concerns some saw exam. The Wall Street Journal. Online at https://www.wsj.com/articles/sat-canceled-in-china-and-macau-over-concerns-some-saw-exam-1453420325

Cohen, Z., & Marquardt, A. (2019, February). US intelligence warns China is using student spies to steal secrets. CNN. Online at https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/01/politics/us-intelligence-chinese-student-espionage/index.html

Coudriet, C. (2019, February). The top 50 schools for international students 2019: foreign enrollment is slowing, but it’s not all Trump. Forbes. Online at https://www.forbes.com/sites/cartercoudriet/2019/02/11/the-top-50-schools-for-international-students-foreign-enrollment-is-slowing-but-its-not-all-trump/?sh=164c27536f75

International Dimensions of UK Higher Education (IDUKHE). (2020, October). International facts and figures 2020. Universities UK. Online at https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/international-facts-figures-2020.aspx.

Lei, R.T. (2017, July). Beijing students take SAT, CAT abroad. China Daily. Online at https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-07/18/content_30151228.htm.

Liu, L. (2017, July). The minimum expenditure by Chinese students taking SAT abroad. Sina Education. Online at http://edu.sina.com.cn/yyks/2017-07-20/doc-ifyihrit0846539.shtml.

Loizos, C. (2020, November). Report: US visas granted to students from mainland China have plummeted 99% since April. Tech Crunch. Online at https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/03/report-u-s-visas-granted-to-students-from-mainland-china-have-plummeted-99-since-april/.

Ministry of Education of China (MEC). (2017, November). The 2017 report on status of Chinese students pursuing higher education abroad. Cernet. Online at https://www.eol.cn/html/lx/report2017/.

Niewenhuis, L. (2019, September) ‘Drops of one-fifth or more’ in Chinese student enrollment at American universities. SupChina. Online at https://supchina.com/2019/09/25/drops-of-one-fifth-or-more-in-chinese-student-enrollment-at-american-universities/.

Open Doors. (2020, November). Data came from IIE’s for the academic year of 2019/20. Open Doors. Online at https://opendoorsdata.org/data/international-students/enrollment-trends/.

Redden, E. (2019, July). In the U.K., a surge in Chinese applicants. Inside Higher Ed. Online at https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2019/07/15/surge-chinese-applicants-british-universities.

Royce, M. (2019, August). Chinese students are valued in the US, says US Assistant Secretary of State. ICEF Monitor. Online at https://monitor.icef.com/2019/08/chinese-students-are-valued-in-the-us-says-us-assistant-secretary-of-state/.

Shan, L. (2020, September). The status and trend of Chinese students choosing higher education abroad in 2019. Iimedia. Online at https://www.iimedia.cn/c1020/74107.html.

Skinner, M. (2019, December). The financial risk of overreliance on Chinese student enrollment. Research Associate, WES. Online at https://wenr.wes.org/2019/12/the-financial-risk-of-overreliance-on-chinese-student-enrollment.

Xiao, B. (2020, November). The number of Chinese students attending the SAT test each year. Global Education. Online at https://www.qinxue365.com/wenda/652836.html.

Xin, D.F. (2019, September). Acceptance of IELTS in China. Zhihu. Online at https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/82645178.

Yeung, P. (2018, December). How English testing is failing Chinese students by driving numbers, not proficiency. South China Morning Post. Online at https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/united-states/article/2177403/how-english-testing-failing-chinese-students.

Zhang, H.W. (2020, April). Chinese students are aspiring resume of SAT test sites in the mainland of China. Envision Overseas. Online at http://www.ilongre.com/qita/news/8845.

About the Author

Dr. YZ Wan has been a full professor for Chinese universities over 15 years, during which he was in charge of international joint-degree programmes. You are welcome to contact him to exchange ideas through his email: wyz689@hotmail.com.

Comments

Post a Comment